By Jason King , Senior Writer Aug 13, 2015

When the Baylor Bears departed Waco, Texas, for a four-game exhibition tour of Canada on Wednesday, freshman guard King McClure wasn’t with them.

Instead, the jewel of the school’s 2015 recruiting class returned to his native Dallas, disappointed he wasn’t with his teammates—but thankful he’s still on the roster and medically cleared to play.

It was just more than two months ago, on June 8, when a doctor delivered news that McClure could hardly fathom.

“He told me it was over,” McClure told Bleacher Report by phone this week. “He told me my basketball career was done.”

An echocardiogram and EKG performed earlier that day revealed McClure had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a condition that affects the muscle of the heart.

While most people with HCM lead normal lives, the disease can be fatal for athletes, as strenuous activity can cause sudden cardiac arrest. The most notable example is former Loyola Marymount star Hank Gathers, whose on-court death in 1990 was attributed to HCM.

Disappointing as the diagnosis was, McClure—ESPN.com’s 36th-ranked player in the Class of 2015—refused to accept that he’d played his last game.

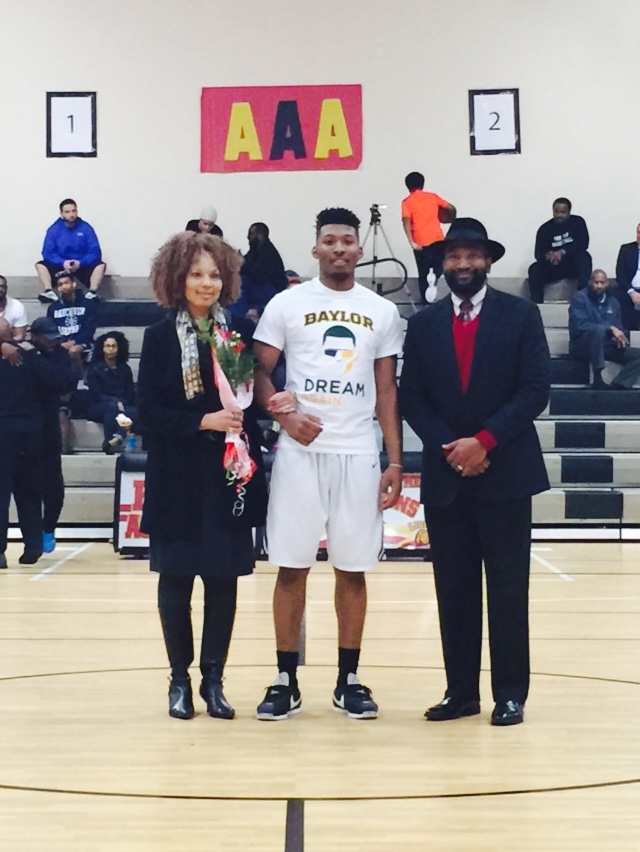

Courtesy of the McClure family

With some help from Baylor’s coaches and medical staff, McClure and his family began researching the disease while seeking second opinions from heart specialists across the country.

“I just encouraged him to rely on his faith and to call on Jesus,” McClure’s father, Leroy, said. “Our emotions went from one extreme to the other. Through it all, we felt the Lord wouldn’t put anything on us that we couldn’t handle.”

Things looked bleak following a June trip to Seattle, where a doctor echoed the sentiments of the Waco physician and advised McClure to stop playing. But later that afternoon, as he prepared to board his flight back to Texas, McClure received a call from former New Orleans Pelicans head coach Monty Williams.

Now an assistant with the Oklahoma City Thunder, Williams played nine seasons in the NBA despite having HCM. He prayed with McClure over the phone and then passed along the name of his Maryland-based doctor. McClure flew in for an appointment and suddenly had new hope.

“He told me it wasn’t over,” McClure said.

Indeed, the doctor informed the McClures that HCM affects people differently, that everyone has an individualized “flavor” of the disease. King, they were told, possessed an extremely mild form of HCM and that he shouldn’t give up on his quest to return to the court.

The McClures shared the encouraging news with Baylor’s staff, who then contacted Dr. Michael Ackerman, an HCM specialist at the prestigious Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. It wasn’t long before they’d secured McClure an appointment.

Courtesy of the McClure family.

“What Baylor did for my son…I’ve never seen anything like it,” Leroy McClure said. “They told us they’d do whatever it took to help him, even if it meant going international.”

Dr. Ackerman studied the results of the tests McClure took in Waco and then repeated them. He also ran tests on McClure’s parents and questioned them about their family history. HCM is believed to be hereditary, yet the McClures said their family has no history of heart problems.

“It was very difficult for us to grasp,” Yvette McClure, King’s mother, said. “Here was this healthy boy with no symptoms, playing AAU basketball for years at the highest level…it’s just hard to believe that something was wrong, that he was sick and we didn’t know it.”

Leroy McClure said it was jarring to think that his son had been competing with the disease all these years. He’s thankful to Baylor for detecting King’s condition through the mandatory heart screening it requires for all of its basketball players, a practice it adopted two years ago.

“We just thank God for his grace, for watching over him all those years,” Leroy said. “It makes you say, ‘Hallelujah.'”

“I want you to tell me that I can play basketball for Baylor University,” King said.

Ackerman smiled.

“You can play basketball again,” said Ackerman, who was moved by his patient’s reaction.

“Part of his life had been sucked away from him,” Ackerman said. “For two months, he was dealing with the prospect of losing something that he viewed as being equivalent to oxygen.

“Hearing that news breathed life back into him. It was like a profound weight had been lifted from his shoulders.”

“Given King’s flavor of HCM, his chance of experiencing an HCM episode that could be life-threatening is about 1 to 2 percent per year,” Ackerman said.

Ackerman added that “preventative measures” have been put in place that have a 95 percent likelihood of countering or aborting the problem “should that 1 percent become a reality.”

“Some people would look at that 1 percent and say, ‘Are you crazy? That’s still high. I’m never playing again,'” Ackerman said. “Other people would say, “That’s all my risk is? 1 percent? I think that favors me continuing to play.’

“Every family ought to have the right to make that decision.”

Reached Wednesday, Baylor coach Scott Drew confirmed to B/R that McClure was treated for HCM and said that, based on Ackerman’s recommendation, he’s comfortable with McClure playing for the Bears. Citing doctor-patient confidentiality, Drew declined to discuss the situation further and deferred all questions to Ackerman and McClure’s family.

Charlie Riedel/Associated Press

Ackerman praised Drew and Baylor’s staff for implementing mandatory heart screening for their players and also for their reaction to King’s condition.

“It’s very refreshing approach, a textbook example of how this should work,” Ackerman said. “There are many screening programs where the intent is to screen, identify and disqualify.

“Their approach is to screen, identify the athlete who may have a condition that predisposes them to sudden death and then get them into the hands of the right people who can make assessment to the nature of the disease, the risk associated with it and the treatment options that might allow the athlete to continue doing what he loves.”

McClure, who has yet to practice with his Baylor teammates, will begin classes later this month and hopes to be in playing shape by the time the Bears officially begin practice in October. A shooting guard and high-level scorer—he made 11 three-pointers in a game last spring—McClure is expected to vie for a starting position in Baylor’s backcourt as a freshman.

“I can’t say ‘thank you’ enough to all the people that supported me,” McClure said. “My parents, the coaches and medical staff and Baylor, my doctors…they stayed by my side and lifted me up.”

Important as basketball is to McClure, the events of the past two months have made him realize that there are even bigger things for which to be thankful.

“We feel like this has done more than prolong his basketball career,” Yvette McClure said. “This has helped prolong his life.”

Jason King covers college sports for Bleacher Report. You can follow him on Twitter @JasonKingBR.